took a poetry class—my first one ever—two years ago during National Poetry Month, in the thick of the pandemic when throngs of people feeling cooped up in an enduring lockdown were trying all sorts of new things. As some found creative and gastronomic outlets by churning out sourdough loaves or whipping up Dalgona coffee, I left kitchen experiments to the experts and kept to my writing comfort zone.

Though a writer for more than two decades by that point, writing poetry was new to me. In my internet search to find my first poetry workshop, I came upon one offered through Cleaver Magazine that felt like a perfect introduction for me to try. That’s where I met Cleaver’s Senior Poetry Editor Claire Oleson, our guest this month. In addition to heading up the literary journal’s poetry section, Claire is an instructor for Cleaver’s workshop series. The class I took with her in 2021 was called “Poetic Anatomies” and it hooked me. I’m happy to reconnect with Claire, especially in this month that celebrates all things poetry.

Let’s start with a quick look at Cleaver’s mission statement:

Cleaver is a Philadelphia-based online magazine that provides a platform for writers and artists producing work of the highest quality. Cleaver exists to:

- elevate emerging voices, including young adults, alongside established writers.

- showcase Philadelphia literary voices among national and international literary artists.

- develop the editorial skills of young writers through our selective internship program.

- present balanced, insightful book reviews promoting work published by small presses as well as often-overlooked works in translation.

- represent the fullest diversity of literary art for all genres and content, advancing emerging contemporary literary forms.

About our name: “cleave” is a Janus word, also known as an “auto-antonym,” meaning both itself and its opposite. To “cleave” is both to stick tight and to fall away. A cleaver is the most broad-edged and brutally efficient kitchen knife, designed to be swung like a hammer for the most effective channel of force. “Cleave” also means to come together with strong attachment.

Good news, WOW! writers: submissions are rolling. Cleaver accepts poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction through Submittable year-round. They also accept craft essays by pitching editors directly.

WOW: Welcome, Claire! I’ll start off by saying how much I love Cleaver’s name and logo. Among the cast of what sometimes feels like thousands in the literary journal landscape, the meat cleaver is quite memorable. The word “Thwack!” just adds to the fun. It’s definitely in my Top 5 for journal logos.

Claire: Hello! So lovely to speak with you.

WOW: While reading the journal’s mission statement, this phrase jumped out at me: To “cleave” is both to stick tight and to fall away. I’d love to hear your take on if the art of poetry is a bit like the namesake of this journal: an “auto-antonym” in a way? Is poetry both itself and its opposite?

Claire: I think poetry can be a self-eating thing. It can be a space of joining and divorce, but perhaps above all, it flourishes best when we struggle at defining it easily. Letting it go like a dog you’re trusting to come back is a great way to trace out its bounds (or, lack thereof).

WOW: I’m visualizing the unbounded joy dogs have, while exploring. That’s a great metaphor! OK, let’s start with Cleaver’s workshops. Writers can choose from poetry, fiction, and CNF classes throughout the year. What do you most enjoy about teaching? What do you think makes Cleaver classes special?

Claire: The freedom Cleaver has given its teachers is fantastic; syllabi are unique, tailored, and allowed to be exactly in the instructor’s wheelhouse of expertise and passion. This has allowed me to cycle through a lot of completely different lenses when considering how to approach poetry as a contemporary and historical, established and shifting, object. I think Cleaver’s classes are unique for the liberatory trust placed in the instructors. They become sites of voice rather than pedagogy and hopefully students find it worthwhile to engage and return because they can find an instructor and a cohort that they trust with the wild west of a personal syllabus.

WOW: Do you have a favorite workshop you teach? Why? And, how do you keep things fresh with repeat workshops?

Claire: I feel lucky to say that the workshops will always feel fresh when the student body changes, even just by one person. An invitation to return to the same writings or a similar lens changes greatly for me as the conversations are led and moved by the participants and where their interest hooks on. At the end of the day, these are generative workshops, and the reading materials are fertilizer and exposure to what is possible in language, where the landscape of poetry can keep going past the horizon we previously used to hem it in.

My favorite workshop to run is likely either the short fiction workshop I taught most recently or the ekphrastic poetry course; getting to see that space between the bodies of visual art and poetry, and how we might use language to illuminate and transform rather than translate or describe, is such an enriching thing to discuss and engage with. That, and I’m continually exposed to new artists and writers to the course and I get to put writers in touch with contemporary visual artists who I think are doing astonishing work.

WOW: Your ekphrastic poetry class sounds stimulating! I’ll keep it in mind. I loved your Poetic Anatomies workshop. It was a great “taste test” for me, introducing me to writing everything from a haibun, to a sonnet, to a sestina, to a villanelle—not to be confused, keeping with my taste test metaphor, with vanilla. [wink]

I have pages of notes that I jotted from your lessons and recommended readings. Looking back, I highlighted this:

Stanzas are the rooms we move through as reader, and the breaks between them can act as hallways and breaths before the next thought.

Rooms we move through. Hallways and breaths. I love that. It’s a great way to frame how we can read poetry. What do you suggest we keep in mind when writing poetry? What do all, or most, poems share to make a lasting impression?

Claire: I think the note I give most often is to push for specificity. Personalizing the rooms, adding your blankets to the beds, your shoes to the hallway, is going to ensure what is being written is coming from a place and an intention rather than the mere expectation of how we think a poem should sound. This is why some of the best individual lines of poetry may come from children, who don’t yet know the expected cadences, anatomies, conventions, and limits. Their language gets to cleave from those instinctual and often limiting habits, and may come away as the freshest thing we’ve read in a long time. We could all do with more liberation and more intention. Those things may sound like opposing animals, but I think they can run well together. By liberation, I mean the ability to see what we blindly do, the ways apples are assumed to be red and our stanzas are assumed to arrive in neat bundles, and to ask if we are abiding by expectation or choosing it. Here’s where intention comes in: when we push to see more, we can become actors in choices we didn’t even realize we were opting out of. This goes for fiction and nonfiction too.

WOW: That’s a great observation about children and their off-the-cuff phrasings and unexpected wisdom. Reminds me of the saying, “Out of the mouths of babes.” But what I most love about your advice is to remember to write with intention, across all forms.

“... push for specificity [in writing]. Personalizing the rooms, adding your blankets to the beds, your shoes to the hallway, is going to ensure what is being written is coming from a place and an intention rather than the mere expectation of how we think a poem should sound.”

WOW: My favorite form you introduced me to is the prose poem. I love that although these poems look like unassuming paragraphs, each one hides a vast iceberg beneath the tips above water. I have notes from early drafts of prose poems I workshopped in your class where you suggested I could try using color as an anchor to make leaps in my stream of conciousness. The poem I was workshopping was about a metal birdhouse painted in blocks of bright blue, red, and yellow. After the class ended, I went on to create a series of prose poems with colored emotions or colored actions as my anchors. Several have since been published, including these two with the online journal Gastropoda, and this one with Unstamatic. Can you share with our readers more tips on what prose poetry could include that might be unexpected?

Claire: So lovely to see your pieces in the wild, thank you! I think we are all caged by what we think is possible in ways that we don’t even see. Reading widely is a great salve to this, and reading fiction while writing poetry or vice versa can be a great way to get out of the literal application of reading (reading poetry to see what’s possible in poetry) to the more impressionistic and personally digested (engaging with one form to see what light, what feeling, what bodies it can give to another.) Prose poetry gets life from that exposure and the expectations readers bring when they see a block of text on the page, anticipating narrative.

As for what prose poets can do, they can read. Start with:

dear white america, by Danez Smith

The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On, by Franny Choi

You are Jeff, by Richard Siken

There’s so much good work out there it’s baffling, so those are just some I go back to when talking about this form and where it can let you go. It’s a form to have a car in, to keep driving, to open the glovebox and take things out you forgot you owned, things you were keeping without meaning to. I’d conclude by saying let your prose poem thrash between list, photograph, inventory, triage, and narrative. Then find where you want to tape it down, if anywhere. It’s a fun form that looks like it’s divorced from form, and that’s how we know that it, and form, had a marriage to divorce from in the first place. There is always a relationship.

WOW: The first two examples are stunning in their language, and devastating in their messages. This line, in Smith’s dear white america: “now he’s breathing, now he don’t. abra-cadaver.” The repetition in Choi’s poem. Both are incredible. As for Siken’s You Are Jeff, it feels like I imagine an acid trip might go down—not that I’d know!

I always like to ask this question of the poetry editors we interview each April, as we celebrate National Poetry Month. What do you think makes poetry poetry? Is it mood? Musicality? Message?

Claire: I think we have to trust it with itself and give perhaps a recursive, frustrating answer. It’s a poem because it’s a poem.

WOW: I read something recently that suggested poetry is often an argument one has with oneself. What’s your take?

Claire: I think that’s a nice possible view! It always feels like a kind of match, a stare-down, to me when I first start. “Argument” does feel like it pushes one mood into the act of it, but I can definitely see that sentence applying to a lot of writing and trying to write.

WOW: How long have you been Senior Poetry Editor with Cleaver, and what led you to the journal?

Claire: I started working for Cleaver as a volunteer, reading in undergrad. It’s been a few years since I became their poetry editor but what’s funny is I don’t have one date. Like a lot of volunteer work for a journal, it’s a watery ascension about what time you can put in, how much you’re willing to read, and how eager you are to attempt to enfranchise and uplift emerging and established writers whose work deserves readership. It’s a joy.

WOW: How far do you have to read in a poetry submission to know whether or not it’s a good fit for Cleaver? What usually tells you a piece fits with the journal’s aesthetic?

Claire: I read all of every poem we receive. I’ll go through to the end before I really decide. Cleaver has given me a lot of freedom in selection, so I also attempt to build issues where the poems feel in some conversation with one another, and an act of curation feels palpable in reading them together. It’s a delight when they enrich one another.

WOW: I agree, it’s rewarding as an editor—I’m the Flash Nonfiction editor for Barren Magazine—to find pieces that fit together and are able to have that “conversation” you mention. We always like to share with our readers how journals differentiate themselves. What do you think sets Cleaver apart?

Claire: My problem is I think there are so many fantastic journals that are alive right now. I think Cleaver does a lovely job of selecting and nurturing work and, at every turn we can, I try to see where I can push accessibility and engagement. Another freedom Cleaver has allowed me: choosing to always have “scholarship” or free seats in my classes which we offer without asking for proof of financial burden. As far as the work Cleaver puts forth, I’m often delighted to see what work other editors have pulled and I think Cleaver is unique in the conversation between pieces within genres.

WOW: We also love to promote other writers. What poems from Cleaver have stayed with you, and why?

Claire: There are deserving pieces and writers who I won’t be able to list, but here are some voices and work you should definitely check out!

travis tate’s Where I Wait for You, published in Issue 32, for its deeply sweet and human landscapes, its peripheral vision on intimacy, and how it holds the everyday up as a gleaming, fantastic thing.

Valerie Loveland’s I Am That Group of Pictures of Spiderwebs Made by Spiders on Different Drugs, published in issue 33, for its clarity of self-diagnosis and haze of self-treatment; its professionalism and knowledge and where it holds intentional, unknown space up, glowing.

Varun Shetty’s O, published in issue 39, for its marriage of medical and lingual experience. The transposition of language on life itself. It is an open, available piece that showcases remarkable content in a small, bright room.

WOW: Beautiful pieces, Claire! Thank you for sharing those. Let’s turn the tables now from the journal to you, personally. How do you approach writing poems? How long does it take you, on average, to get a poem to where you feel it’s finished? How do you know?

Claire: I think the time varies wildly. Some it’s a ten-minute sprint, others, I get a line and then leave it alone for months or years. Get ready for another annoying answer: I think it’s done when it’s done. I think you have to wade in, take the temperature of the water, and know.

“I think Cleaver does a lovely job of selecting and nurturing work and, at every turn we can, I try to see where I can push accessibility and engagement. I’m often delighted to see what work other editors have pulled and I think Cleaver is unique in the conversation between pieces within genres.”

WOW: Do you have a favorite poetry form?

Claire: Not a hard and fast one, but I do love prose poetry for its freedoms and intentions. A good sestina, though, can really do you in, if you let it.

WOW: Tell us about your first publication. The thrill of it.

Claire: I think my first publication was in the second or third issue of Siblíní Journal, local to my hometown, when I was in high school. I’m delighted to tell you it is no longer available, and we are all saved from having to know it. I got an email while on a trip with limited internet access. It was extremely exciting not for the little piece, but for the realization of what feels possible, that I could keep writing. I don’t recommend using publication in this way: so many fantastic things go unpublished and many bad pieces see hardback editions. Let it be fun, if you can, to send work out and see where it sticks.

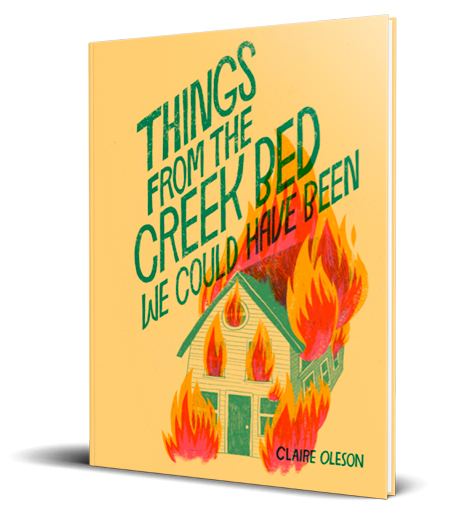

WOW: You authored a chapbook titled Things From the Creek Bed We Could Have Been that won the 2019 Newfound Prose Prize. The prize is awarded annually to a chapbook-length work of exceptional fiction or nonfiction that explores how place shapes identity, imagination, and understanding. Can you tell us more about the origin for your chapbook, and how it explores place and identity? And, what did you most enjoy about working with Newfound as a publisher?

Claire: Newfound is a fantastic small press in Texas full of talent and kindness. Crystal Odelle, their director, is smart and so generous with her time and expertise. I can’t recommend working with Newfound enough. Most of the work in my chapbook came from undergraduate writing workshops I was lucky to take at Kenyon College. Some came from outside the classroom, but the first story and probably my favorite piece in the collection—titled Alluvium—was one of the first pieces I brought into a workshop setting. The stories in that chapbook approach queerness, the body, and rural, desolate spaces as ways to try and see a self.

WOW: As we close our interview, what do you think poets bring to the world, to help us understand it better?

Claire: Invitations to see and understand things differently. Ways to see how we go about seeing. Fun, terrible, definitionally (mostly) financially unlucrative work. It’s great that I love it. Also, go read Andrew Grace’s poem, Not a Mile, in The New Yorker. He was a professor of mine at Kenyon and deserves more readership, like so many.

My thanks to Cleaver Senior Poetry Editor, Claire Oleson, for joining us. Remember that Cleaver has rolling submissions for poetry, fiction, and CNF. Why not consider submitting one of your poems to Claire and the team to celebrate National Poetry Month?

Until next time!

Ann Kathryn Kelly writes from New Hampshire’s Seacoast region. She’s an editor with Barren Magazine, a columnist with WOW! Women on Writing, and she works in the technology sector. Ann leads writing workshops for a nonprofit that offers therapeutic arts programming to people living with brain injury. Her writing has appeared in a number of literary journals. https://annkkelly.com/.