someone who learns about history through fiction, I’m excited about today’s craft talk for this issue of WOW! Women on Writing. We have a roundup featuring three of our best historical fiction authors, including Clare Beams of The Illness Lesson, D.M. Pulley of No-one’s Home, and Michelle Cameron of Beyond the Ghetto Gates. They have some great advice on how to get started with the writing and research process even if you’ve never written a work of historical fiction before.

Let’s start with an introduction our special guests:

Clare Beams is the author of the story collection, We Show What We Have Learned, which won the Bard Fiction Prize and was a Kirkus Best Debut of 2016, as well as a finalist for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize, the New York Public Library's Young Lions Fiction Award, and the Shirley Jackson Award. She is the author of The Illness Lesson, which was published in February 2020. She lives in Pittsburgh with her husband and two daughters and has taught creative writing at Carnegie Mellon University and St. Vincent College.

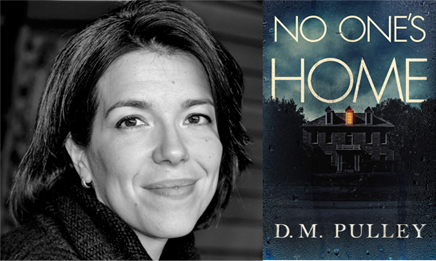

D.M. Pulley lives in northeast Ohio with her husband, two children, and a dog named Hobo. Before becoming a full-time writer, she worked as a professional engineer rehabbing historic structures and conducting forensic investigations of building failures. D.M.’s structural survey of a vacant building in Cleveland inspired her debut novel, The Dead Key, the winner of the 2014 Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award. Since then, Pulley has sold over a half million books worldwide, and her work has been translated into eight different languages.

D.M.’s historical mysteries shine a light into the darker side of life in the Midwest during the twentieth century, when cities like Detroit and Cleveland struggled to survive. Her latest novel, No One’s Home, unravels the disturbing history of an old mansion haunted by family secrets, financial ruin, and murder. The abandoned buildings, haunted houses, and buried past of the Rust Belt continue to inspire her work.

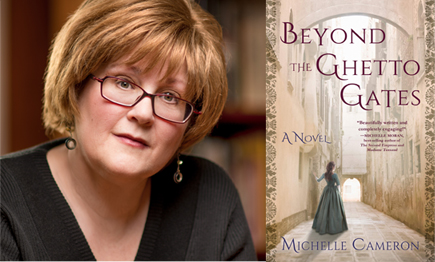

Michelle Cameron is a director of The Writers Circle, an NJ-based organization that offers creative writing programs to children, teens, and adults, and the author of works of historical fiction and poetry: Beyond the Ghetto Gates (She Writes Press, 2020), The Fruit of Her Hands: The Story of Shira of Ashkenaz (Pocket, 2009), and In the Shadow of the Globe (Lit Pot Press, 2003). Her novel, Babylon: A Novel of Jewish Captivity is forthcoming from Wicked Son Press in September 2023. She lived in Israel for fifteen years (including three weeks in a bomb shelter during the Yom Kippur War) and served as an officer in the Israeli army teaching air force cadets technical English. Michelle lives in New Jersey with her husband and has two grown sons of whom she is inordinately proud.

***

WOW: I realize this question might be fun for some more experienced novelists and writers, but it also might be a fearful question for the newer ones. What advice do you have for aspiring historical fiction writers who often fall into the trap of letting historical fact take over their fictional story? Is there a lot of room for freedom?

Clare Beams: I think what worked best for me was to do as much of the actual first-draft writing as I could before and while researching, so that story and research worked in tandem, instead of beginning from a place of historical fact and shaping the story around that fact. I may be a special case, though, since I wasn’t writing about real historical figures but inventing my own (though I did some borrowing from real Transcendentalist figures in crafting my characters, they’re fictional and never really lived)—and since I’m the kind of writer who may set a story in a historical time period but is also apt to invent a strange species of bird to put into said story. I think there’s as much room for freedom as a writer decides to take, as long as the writer earns that freedom. Different kinds of historical fiction have different terms and different demands.

WOW: I love the hybrid version of your answer. What do you think Michelle? Is there room for creativity and freedom when writing historical fiction?

Michelle Cameron: There’s definitely room for freedom—but not at the expense of completely altering the history! (That’s called alternative history and is a genre all to itself.) I’m a strong believer in putting story first—as in Beyond the Ghetto Gates, where I condensed actual events to occur before they really did for the dramatic impact in the climax of my novel. But if you do that, you have an obligation to let the reader know in your Author’s Note.

What I find often is the tendency of historical novelists to discover and become completely enraptured by some tidbit of history—often some aspect of life—and offer it up in full and exhausting detail to the reader, whom they assume will be as intrigued by it as they were. Generally this type of “history dump” detracts from the story and can bore the reader. New historical novelists need to wary of including too much of their research!

WOW: I agree. The role of research definitely has its place in writing. What do you think D.M.? How do you see the balance between research and writing?

D.M. Pulley: I try to ask myself several questions before I begin the research and then again throughout the writing process to keep myself on the straight and narrow. The first and most important question is: what is the story about? The second question is: do the historical details serve the plot and move the story forward? Lastly, I ask myself: is it true or true enough?

Done well, historical fiction can add a sense of realism to a plot and open a window to another time. Done poorly, it can leave a reader feeling betrayed. Inaccuracies ruin a reader's suspension of disbelief and take them out of the story, so I try my best to avoid anachronisms and fudging facts in my depictions of the past. The line between true and true enough is often fuzzy, but I research my historical period thoroughly so that when I deviate from the facts, it is a conscious choice and not a mistake.

Accuracy aside, if the historical research isn't essential to the story itself, I leave it out. I do not want my fiction to read like a textbook. I don't want to bog the reader down with an abundance of information and unnecessary detail. Instead, I like to use history in all its strangeness as a springboard for my plots, as a backdrop for my characters, and as the setting that will give meaning and context to the narrative. Luckily for me, history is a key ingredient for the types of Gothic-themed thrillers I like to write. What is a haunted house without its dark past? What is a Rust Belt town without its troubled history? What is a family without its skeletons?

“My advice would be to find one character, one mystery, one crime that you find meaningful in the avalanche of information out there. Find that one keyhole into a time and place and stay focused on that little window.” ~ D.M. Pulley

WOW: What a well-rounded way to approach research. I hope this gives writers out there the confidence they need to not perfect the research. Now let’s take a look at characterization in light of the research. Clare, let’s start with you. How did you ensure that your research was also true to your characters?

Clare: Because I didn’t undertake a long research period before I started writing but did the research during the writing itself, characters and research sort of developed together. And I think here I was also helped by the fact that Caroline and Samuel and Hawkins and David were never real people. That is, I wasn’t really contending with a bulk of information about people’s real lives that I then had to stuff inside fictional contours; the fictional contours were the defining ones from the beginning.

WOW: That’s a helpful way to think about it—research and characterization as a natural tie-in. I love what you’re saying about “stuffing fictional contours.” Michelle, how does research play out in your characters?

Michelle: Many of my characters are completely fictional people who simply lived during that time, which does make it easier. But for characters that are factual—such as Napoleon—you have to rely on the records of what he himself said, in public and in private. Napoleon was a mercurial creature, full of passion and hugely invested with what he saw as his personal destiny. Because of that, he was also impatient and even aggressive when he perceived something or someone getting in his way. I was fortunate that we have so many examples of his speeches, as well as his secretary Bourrienne’s account of what he said in private, among other accounts.

WOW: How fortunate for you that you had access to this information. That can make things a bit easier. How did you build on your character's conflict as the main conflict in your story?

Michelle: I did this by constantly asking myself: what do my characters want? What’s standing in the way of that—and how can I use the history to provide additional obstacles? That’s what conflict is, really—denying your characters what they want and helping them grow through the conflicts they face and the choices they make. And then, by the time the novel closes, they may actually achieve their initial aspiration—or if not, realize why they couldn’t.

WOW: Those are very helpful questions for aspiring historical fiction writers. I especially love tapping into history to provide additional obstacles. I’m curious to know how you, D.M., use the historical past to create tension with your characters.

D.M.: The way the past can haunt the present is a recurring theme in all of my stories. My present-day characters often must follow in the footsteps of people that came before if they want to unravel the mysteries that plague them. Iris Latch must chase the trail of a 1970s secretary through an abandoned office building in The Dead Key to find out who owns the building and what they're hiding. In The Buried Book, Jasper Leary must uncover the clues his missing mother left behind in the wreckage of her childhood home to find her. Hunter Spielman must track down the former owners of No One's Home to find out if the house is truly haunted. By making the clues of the past critical to solving the mysteries of the present, the struggles of my historical characters become essential to my stories.

WOW: I love how you use the clues of the past to solve a present mystery. That’s really cool. Clare, what about you? How did you build on your character's conflict as the main conflict in your story?

Clare: Because my characters aren’t actual historical figures their conflict was only ever entirely their own. But I would say that certain aspects of my research ended up informing my novel’s central conflicts in ways I couldn’t have anticipated before doing that research. I did not, for instance, know anything about historical treatments for mass hysteria before I began writing and researching The Illness Lesson, and those treatments end up figuring heavily in the central moral dilemma of the book.

“For me it worked well to tackle the writing and research simultaneously, so that they reinforced each other.” ~ Clare Beams

WOW: I guess there’s so much that plays out in the actual writing process that can’t be anticipated. Let’s talk about another fictional element. In terms of setting, how much did you lean on research to ensure you were creating an accurate historical backdrop for your story and your character?

Clare: I did do a lot of setting-based research, and the seeds of the novel came from visiting Fruitlands, where Bronson Alcott founded a failed commune during his daughter Louisa May Alcott’s childhood. And I think here, too, I did a lot of research I didn’t know was research, just by living my particular life up to the point at which I began writing this novel: I grew up in Connecticut, in a house from the 1700s and a town that was founded in the 1600s; I adored Little Women and read it many many times as a kid, etc. I did my more deliberate research as the need arose; I would write until I ran into something I didn’t know, or sort of write around questions where I could and then go back to make sure I wasn’t, say, serving my characters entirely the wrong kind of food, etc.

But I’m not the kind of historical fiction writer who’s especially drawn to long pieces of historical description—those often end up feeling a little inert to me as a reader. I most love historical fiction that’s in the vein of Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Blue Flower, where you trust absolutely that the detail you’re given is accurate, but you’re no more likely to hear about the particulars of a house’s furnishings or the nature of the period’s transportation system than you would be in a contemporary novel. After all, the characters find those details no more worth remarking on than you or I would in the context of our own lives.

WOW: Right on. And I think that the setting has to be woven in a way that makes the story organic. I’m not a fan of long descriptions either. I get easily lost in the story. What about you Michelle? How do you handle setting with regard to historical fiction?

Michelle: I set up a Pinterest board which I divided into different categories, such as fashion and furniture, artwork from the period, scenes from Ancona itself, and Napoleon in Italy. That was a huge help when I wanted to take another look at an item of clothing or how I was decorating a room—or even a battle scene—to be able to accurately describe it. I also visited museums, especially those that outfit an entire period room such as the Met, and minutely examined such items as glass and silver, ceramics, coins, clothing, and of course statuary and portraiture. As I said earlier, my bookshelves are crowded with research books, including such gems as a book describing the Italian campaign which also displayed pictures of the uniforms of well-dressed soldiers or recipes for the Elizabethan family. Even on-line sources were useful—such as the one that told me that Napoleon’s favorite meal was roast chicken and beans. I definitely included that detail!

“One huge tip is to download a calendar from the particular year(s) and use it to keep track of holidays, etc. It’s easy to find calendar blanks online.” ~ Michelle Cameron

WOW: I love the idea of setting up a Pinterest board. What a great visual tool! It sounds like you did quite a bit of research for your novel’s setting. D.M. Pulley, how did you research the setting for your books?

D.M.: Researching a time and place from the comfort of my home or library provides mountains of facts and figures, but nothing I read can fully replace first-hand experience. I make it a point to visit the places I'm writing about to really understand their sounds, smells, and tastes. I spent weeks working in the building that inspired The Dead Key. I spent hours in the barn of a working farm researching The Buried Book. I lived in the old factory where The Unclaimed Victim takes place for two weeks. For my latest novel No One's Home, I set the story in an old mansion modeled after several old houses I helped renovate while working as an engineer. Without immersing myself physically in the settings of my stories, I would've struggled to bring them to life.

WOW: So cool! I love how immersed you were physically and not just as a researcher. Lastly, what are some tips for writing historical fiction? Any last words you’d like to share?

Clare: For me it worked well to tackle the writing and research simultaneously, so that they reinforced each other. Every writer is different, but I think had I attempted to do all the research I thought I’d need first, I might have risked researching for years and never getting started at all.

WOW: That is a very smart way to go about it—tackling both the writing and research otherwise you get into what I call “perfection paralysis,” and you never get started writing. What about you D.M.?

D.M.: The past is so full of stories to tell, it can be overwhelming. My advice would be to find one character, one mystery, one crime that you find meaningful in the avalanche of information out there. Find that one keyhole into a time and place and stay focused on that little window. You can only tell so many stories at a time. Once you find the story, research long enough and hard enough that when you close your eyes, you can see the scenes clearly.

WOW: I love how you phrased that: “find that one keyhole into a time and place and stay focused on that little window.” Beautiful! Michelle, you’re last. What about you?

Michelle: Do your homework and read, read, read. Take copious notes and organize them so you can find them when they’re actually needed. (A lot of my writing students swear by Scrivener, which I’ve never used, but which sounds like it might be a huge help in this regard.)

When you come across applicable images, save them for future reference. That way, when you’re struggling to describe a dress or a room, you can study them more carefully. Create a private Pinterest board if you don’t want to reveal what you’re researching to the world.

Also, I create a multi-faceted timeline for all of my novels—important historical events, highlighting the ones that have bearing on my plotline, as well as the fictional events I create, and any backstory events that might come into play. That helps me keep everything straight because sometimes the chronology can get confused! One huge tip is to download a calendar from the particular year(s) and use it to keep track of holidays, etc. It’s easy to find calendar blanks online. For me, it was important that my characters didn’t so something on Saturdays that Jews of that period wouldn’t do on the Shabbat—and then once, it was critical that my heroine did. So knowing those Saturday dates was incredibly helpful.

WOW: Great tips for staying organized. I can see how incredibly challenging this can be. Thank you all so much! Your responses and advice are so helpful for aspiring and veteran writers alike.

***

Dorit Sasson is an Israeli-American writer and the award-winning author of Accidental Soldier: A Memoir of Service and Sacrifice in the Israel Defense Forces and Sand and Steel: A Memoir of Longing and Finding Home. Her work has been featured in The Writer, Kveller, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Ravishly, The Wisdom Daily, SheKnows, and HuffPost. She also supports small businesses, companies, and organizations with their SEO copywriting needs. Visit her website at DoritSasson.com.