Often, when I write an essay, my mind goes blank.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Blank, not blink, though at times a blink can be a kind of blank and then blonk. A new word! New idea. At times, it’s the onomatopoeia that saves an essay’s beginning.

*

(I cast on an idea.)

*

Because blonk is the sound of a thought thunking itself down on the page, and it’s the blank (mind) that led it here.

*

“Cast on” as in yarn. As in looping the yarn onto the needle, so I can start knitting and weaving things together. I just took a knitting break from this essay because I needed to slow down and think a bit, even with the blinking blanks and the blonk gaining existence. I casted on my yarn then and did a row. (*K6, YO, K2TOG*—and while knitters will know what that means, non-knitters can be in the know just by knowing that there are patterns to knitting, like there are patterns to writing. And it’s in the writing and sorting through the patterning that we can find our vibe, our flow, the words that pour forth because within the fragments, the mosaics, those blank spaces that make up the lyric essays that live within us, we can find the flow. Even in the pieces. Even in the blanks.) “YO” in knitting is a yarn over. It’s when you swing the yarn over the needle, and eventually that becomes a hole and eventually the holes create a whole pattern.

Holes like breathing spaces ______ that make you feel whole.

Which is to say it’s okay to take your time when writing, when figuring.

*

Patrick Madden says this about writers and patterns: “We are a pattern-finding species, perhaps none of us more so than essayists, whose job it is to corral bits of raw experience into meaning without inventing rounded scenarios and uncanny coincidences. Our imaginations don’t supply the materials, but they make the connections.”

*

In knitting patterns, the parentheses are for what needs to be repeated. This last knitting break I did eight repeats of *(YO, K1) x2, YO, K3, K2TOG* Which is to say there’s a type of rhythm found in whispering to myself: “Yarn over one; yarn over one; yarn over one, two, three; two together,” as I go through the round, as motions match repetition. Like it’s a prayer, a meditation. A mindfulness of object in hand, fingers guiding the creation.

Like how my pen feels when I write with it. Like how I’ve been trying to write an essay that looks like knitting, but I don’t really know what that means. I can feel it, though. Know it. Explore it.

*

The lyric essay is an act of observation. What it is to look, listen, spy on life’s tacit trembles and inner-workings, record, then translate, and craft into lyricism. It’s not about turning life into art, turning yarn into fabric, but it’s about the witnessing and the creating together, intersecting at the experience of living.

Lyric essayist Dinty Moore has a book about being a mindful writer, aptly named The Mindful Writer. I’ve never read this book, but I mindfully recommend it. That is, I understand the power and importance of observation, of how you can understand something without fully experiencing it, that you can write about the mindfulness that brings you to something—the power of (blank).

*

How the intentional blanks create a pattern in lyric essays.

________.

*

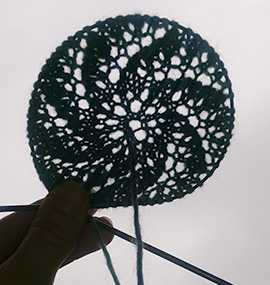

About the blanks: I take another knitting break, so I can consider the blanks. (And I also break to take some pictures because visuals are fun, and this is about patterns after all, which are mostly a visual-ish kind of thing. A pattern I just noticed that’s emerging in this essay: aside from my enthusiasm for using colons, the core of this essay is forming within the parentheticals. Which is interesting because that’s antithetical to the “right” usage of parentheticals. The parenthesis are intended for enclosing the almighty Side Thought. But maybe that’s something lyric essays are all about: finding patterns in punctuation and form and just going with it because that’s just how the mind thinks sometimes. Lyric essays give us the space to break “rules” and go with the flow of the brain on the page. Watch it blonk. And so if the pattern of this essay is colons and core thoughts are within parentheticals: then I’m just going to keep going with it.)

*

Lyric essays are all about exploring the possibilities of ideas. The meaning is in the exploration. The questions raised by the patterns established are their own answers. (The blank space, then, is the consideration. Can I write an essay that looks like knitting?)

*

ME: So this is what I just spent an hour knitting. :) No pattern. Just made the shit up as I went along. New life goal: knit ugly sweaters for lighter cozies!

BOYFRIEND: Like life: make the shit up; and even though it seems random, there’s a pattern of who we are.

*

(Consider.)

*

The lyric essay is observation and consideration and making connections where there might not have been were we not paying attention. It’s a full-body observation. It’s with breath, that is. The way we breathe because of punctuation’s—placement—.

And the white space’s e x h a l a t i o n.

This is the blank, the space, the breath, the pause/chance/opportunity—place—the pace we create to give the reader

(to give ourselves)

that space to

consider.

To observe your reader’s experience when engaged with a lyric essay.

It’s a conversation—

an interaction,

a practice of observation.

Observe.

Because here is the space where ideas connect,

connect to more ideas. The lyric essay plays with form, from this playing, this typing, is a type of paying—the type, the font—the upfront payoff of letting your brain do a bit of wandering

and a bit of wondering.

W@ndering, perhaps.

*

Connections are like patterns, and so it’s not the first stitch or the last stitch we admire, but everything created in-between, the pattern they are nothing but a part of.

Everything I know about knitting I learned from the lyric essay. This isn’t about spinning tales or about yarn unraveling. It’s about the patterns I sense in creation. With lyric essays, sometimes the pattern, the structure of it, comes as you write. This essay, for instance. I didn’t know how this was going to be words and yarn woven together. Lyric-ed together. But as I started writing, the figuring-it-out-as-I-go started to take shape, too. I’m knitting a tank top right now, patternless:

Without a pattern already written, that is. I have the general idea (halter top), the general stitches I’ve learned when knitting other stitches; but beyond that, I’m making it up as I go. This is lyric essaying. The general thought—an inkling for a something that will speak to an other thing, knitting and writing, for instance—and I’m letting the structure make itself up as I go. First, this essay was about the _______s and the yarn overs. Then it was about observation and fibers’ meditations. (And of course: patterns.) Now it’s about this—a structure forming while an idea unravels itself within me. Gloriously.

An inner-methodical mazing through my brain, finishing on the page.

*

There are traditional ways to tell a story. There are lyric ways as well, which is really just a pretty word for a clunky term: “non-traditional.”

*

Knitting break. And now I remember that I came up with a line in my last knitting break that I was going to write down but forgot about it. Then when I re-started knitting, the memory of the fact of the line re-arrived because that’s how brains work.

Memory: Association of thought with activity.

Line: The lyric essay lives, exists within the looking.

The journeying.

Rather than a narrative arc, there’s a narrative exploration. I take my navigation tools, equip myself for the journey’s beginning.

Tools:

- a thought

- a pen

- a page

- a yearning to understand the fabric of words on a page

- a yarn metaphor

- a skein of real yarn in my hands

- a set of needles

- a knowledge of something else

- a curiosity to know how one thing speaks to another

The writer’s job is to journey through all of this, to shape experience into a further exploration. The first and last sentence give the lyric essay context, but it’s what happens in-between where the looking exists.

*

All of this is about craft. It always is. Always will be. Because the purpose of the lyric essay is in its creation. It’s not about the destination; it’s about the journey. I love wearing hats, but I don’t knit them because I’m obsessed with head accessories. I craft them because I’m in love with knitting’s journey.

Creative fibers woven within me.

There’s a flow felt when crafting a lyric essay.

There’s a flow felt when crafting a knitted thing.

There’s a flow felt when crafting a sense of ourselves.

*

So, really, WHAT is a lyric essay?!?

The lyric essay is a type of personal/creative nonfiction essay that focuses on form more than story. That is, the way the story is told is just as important—if not more so—than the story that you are telling. To get a general idea and an actual picture (visuals included!) of what different narratives and personal essay structures can look like, check out Tim Bascom’s essay, “Picturing the Personal Essay.”

There are a number of different kinds of lyric essays, such as:

- The hermit crab essay: The form of the essay takes on an already-established form of writing, such as grocery lists, eviction notices, newspaper errata, job applications, and the like. If the written form already exists and an essay takes on that form (like how a hermit crab can move into any sort of object to make its home in that “shell”), then that’s a hermit crab essay. For a great example of this, see Jill Talbot’s “The Professor of Longing.”

- The segmented essay (sometimes called a mosaic): Asterisks and section breakers are the soul of this kind of essay. Much like this craft essay, “On Lyric Essaying and Casting On,” segmented essays take different thoughts, concepts, reflections, and facts and weave them together with a personal narrative by creating different segments. The segments then begin to speak to one another to provide a larger, fuller narrative. Lia Purpura’s “Autopsy Report” and Chelsey Clammer’s (that’s me!) “Mother Tongue” are great uses of this form.

- The woven essay (sometimes called a collage): Take a slew of thoughts and weave them together with a personal narrative to create a larger story! Much like the segmented essay, this type of essay also brings in concepts and personal narrative, but it isn’t as visually segmented as the, well, segmented essay is. Sound confusing? It’s not. Just kick back and read Eula Biss’s “The Pain Scale” to get your mind blown as you witness the story take shape.

Time to write your own lyric essay!

Here are three writing exercises and a few tips to get you started on your own, unique (both in structure and story) personal narrative:

- Write about your relationship with your parents by filling out a employee performance review.

- Look up your favorite hobby on Wikipedia. Print it out and highlight any of the sentences that are interesting to you for whatever reason. Use those sentences as prompts to write about the person in your life you have loved the most. (This person doesn’t have to have any relation to the hobby. But use your love for the hobby to start writing about your relationship with this person.)

- Write for ten minutes about the story of your birth. Write for ten minutes about the first time you were in love. Write for ten minutes about why you write. Now weave the three together. Use asterisks to break up the different segments!

Tips:

- If you’re trying to write and your brain starts hurting thinking about everything, then start writing about why the exercise is hard. You never know—the writing process for writing the lyric essay could become a part of the lyric essay.

- Include other sentences and quotes from essays or poems that are related to what you are trying to say. Use those sentences or quotes as inspiration to keep writing—perhaps even as writing prompts themselves!

- Don’t be afraid to get weird. Think your reader might not understand? Don’t worry—just keep making the connections that you see, and trust that your reader will see them, too.

- When in doubt, focus on sound. If you aren’t sure what you’re saying, but the words are starting to rhyme or flow together, then keep going with it. Sometimes we have to hear the words before we know what they’re trying to say.

- The biggest thing to being a lyric essayist is observation! Throughout every day, just jot down anything you find interesting. Whether it’s a word or something you overheard or perhaps how your coffee mug looks like something you remember from your childhood, whatever it is, just note the observations your brain is constantly making and use those bits of your life to start writing and collaging together your story.

***

Chelsey Clammer is the award-winning author of Circadian (Red Hen Press, 2017) and BodyHome (Hopewell Publications, 2015). A Pushcart Prize-nominated essayist, she has been published in Salon, Brevity, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, The Normal School, Hobart, The Rumpus, Essay Daily, and Black Warrior Review, among many others. Her third collection of essays, Human Heartbeat Detected, is forthcoming from Red Hen Press. You can read more of her writing at: www.chelseyclammer.com.