“Who hasn’t wondered: am I a monster, or is this what it means to be a person?” This is the question that burns through Monster Portraits, a question that is explored, teased, and unwound but never finds resolution in Sofia Samatar’s hybrid blend of fantasy and memoir.

Sofia is an assistant professor of literature at James Madison University. Her specialties include Arabic literature, African literature, postcolonial literature, Afrofuturism, and speculative fiction. She’s published two novels and a book of short stories with Small Beer Press: award-winning and Nebula finalist A Stranger in Olondria, The Winged Histories, and Tender.

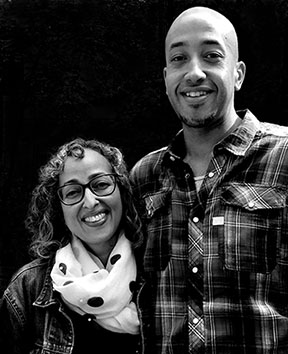

Her latest book Monster Portraits was published in 2018 by Rose Metal Press and is a collaboration with her brother, artist Del Samatar. This book seeks understanding, but not definition, of the human experience of monsters and monstrousness. Sofia agreed to share her thoughts on Monster Portraits as a genre-bending speculative memoir, and how she approaches taboos and challenges and stays true to her artistic vision.

WOW: I have a history of fearing monsters, and I read Monster Portraits with that in mind. I read it emotionally, rather than intellectually, and allowed myself to experience it as a fairy tale, each monster evoking the same question: is this real? Like my experience of fairy tales when I was young, I wanted it to be true, and simultaneously, I was afraid it was. I know you’ve talked about Monster Portraits and speculative memoir in interviews. Could you speak to fact vs. fiction in this story, and how it works as speculative memoir?

Sofia: When I talked about the idea of the speculative memoir over at Electric Literature, with my friends Matthew Cheney, Carmen Maria Machado, and Rosalind Palermo Stevenson, Matt said something I loved: that the speculative should always end with a question mark. There’s a trickiness or slipperiness to this mode that invites questions. Is that true? Did that really happen? That didn’t really happen, did it? At one point in my life, I would have said it doesn’t matter; it’s all just writing, a flow of language, a kind of spectacle. But now I don’t think that way at all. Rather, I think speculative memoir, if it exists, is one of those genres that requires fiction and reality to be separate things. Only if something exists in the world—like myself and my brother, as kids, watching Knight Rider, one of the scenes in Monster Portraits—only then can it clash against fiction in a way that makes sparks. Question marks are a way of indicating those sparks. I think Monster Portraits is a book that radiates question marks. This makes me happy.

WOW: I think it’s really interesting that you chose monsters as the fictional element juxtaposed against your lived experience. What did the text reveal to you about monsters and monstrousness as you wrote it?

Sofia: My brother and I did set out to make a monstrous book: a book with a form that pays homage to its subject. And monsters, of course, combine things that don’t go together; they squirm in the cracks between categories; they proliferate in the blurry regions. If writing this book revealed anything to me about monsters, it’s that they have no end. They exist outside the box, beyond limits. There could always be another. So the book has the feel of a collection that’s incomplete. It ends with this invisible question mark: What next?

“I felt so many shifts, so many places where monsters could be: in ourselves, in others, in nature, in culture.”

WOW: That feels very much like memoir, in that the story doesn’t end when the book does.

One thing that surprised me about Monster Portraits is how it recalled so much of my early life as I read it. When I was growing up, everything felt alive and sentient and monstrous. Because of this hypersensitivity, I was always on guard. Always afraid. Then, as a teen, I began to feel like I was the monstrous one. The objects around me became still and quiet, and my perception of their consciousness died as I developed a sense of myself as the monster in the room: ugly, unbalanced, unwanted, and angry. In my twenties, I began to fantasize that I was actually a monster, and this felt powerful, but also frightening.

When I read Monster Portraits, this feeling returned. The self as a monster is both fearful and powerful. How does writing about monsters break taboos and constraints when we accept monsters and the monstrous as part of our mythological inheritance and acknowledge them as part of ourselves?

Sofia: The first thing I have to do is recommend an amazing short story by Micaela Morrissette called “The Familiars,” which I read in Ann VanderMeer and Jeff VanderMeer’s anthology, The Weird. It really captures what you’re talking about here—that childhood sense of the incredible, almost sinister aliveness of the world, and the shift, as one grows up, in the location of the monstrous. When I was working on Monster Portraits, I felt so many shifts, so many places where monsters could be: in ourselves, in others, in nature, in culture. There were very few things to cling to, to retain a sense of continuity of writing a single book. But one idea I did hold onto was the idea of space, or as the introduction to the book calls it, the field. This for me was the space where the monsters dwell, and it was the space of literature—that was what I was always looking for. And that quest, the feeling of a search for further expanses in the field, further monstrous cities and crags and hotels, holds the book together.

There’s never a clear explanation, though, of why the narrator of the book and her brother have embarked on this particular quest. She says they’re failures. She says they’re looking for a zone of incandescence—a phrase I took from Aimé Césaire, his definition of the space of poetry, of the field. She says that when she was growing up, all the kids on her block loved monsters, but only two of them kept this passion after they grew up. Only she and her brother remain obsessed with monsters as adults. Why? She can’t tell you, and neither can I.

I hope the book answers this question by demonstration rather than explanation. I hope it grants the reader some of the enchantment of the monstrous, the sense of coming close to terrible, beautiful, inexplicable beings, creatures beyond explanation, beyond justification, like all of us.

“I believe readers can feel when someone has had to write defiantly against those messages that say, ‘It can’t be done,’ and that it gives the work a special intensity.”

WOW: You’ve spoken about the need for disinhibition in your writing, that you’re tired of holding yourself back. I find that’s a real struggle for me and for many writers I know. There’s almost something frightening about writing exactly what I want, and I often have to force myself to express myself fully. This fear was strongest during my MFA program, in which experimentation was risky, and the criticism was pretty scathing. What are the messages you carry with you that tell you to hold back, and how have you learned to write through them?

Sofia: Is there ever any value to these messages? Possibly. They provide something to strive against; and in that way, they can energize the work. My favorite writing—by a variety of people, from Virginia Woolf to Roberto Bolaño to Claudia Rankine to T Clutch Fleischmann—has a sense of risk. You feel that the writer has been forced into a position where they have to be extremely daring. I don’t think I’m imagining this. I believe readers can feel when someone has had to write defiantly against those messages that say, “It can’t be done,” and that it gives the work a special intensity.

WOW: When my writing pushes against boundaries and taboos, I sometimes find it difficult to distinguish between self-doubt and reflective critique. Sometimes a scene or a line needs to be cut because it’s just not that good; sometimes a scene or a line is good, but I’m afraid I’ve pushed too far out of the box, and I’m tempted to cut it. I think many writers experience this and struggle with self-censorship and wanting to pull back. Is there ever a point at which you feel like you have gone too far in your writing, and how do you know?

Sofia: I’m not really sure what would constitute “going too far” in writing. I’ve never come up against that. I do understand “writing something bad.” For me, one of the most important elements of the writing practice is time. You have to set your drafts aside, to let them sit. Finish a draft, then put it away for at least six weeks, maybe longer, especially if it’s a big project you’ve been working on for a while. When you return to it, you’ll be amazed at how easy it is to recognize the places where the tone is off or where something fails to do what you intended. Unfortunately, this doesn’t always mean you can fix it! It just means you can recognize it. Not everything can be fixed. I feel like I’ll never write a perfect book; I just hope they go into the world with the flaws I’ve chosen, for the most part, and not errors I didn’t even notice, though there’s no guarantee against that either.

“One of the most important elements of the writing practice is time. You have to set your drafts aside, to let them sit.”

WOW: What’s your strategy for sitting with the fear of pushing boundaries and allowing yourself the freedom to keep pushing?

Sofia: I suppose this is one of the things I tell myself, to give myself the freedom to go on stretching myself in writing. I’ll never write a perfect book. If I’m lucky, though, I will write the books I want. If it’s not going to be perfect anyway, why shouldn’t it be what I want? Why should it be flawed in somebody else’s way?

Also, I realize it’s totally the conventional wisdom on writing to say, “Set your draft aside for six weeks,” but it bears repeating because of the pressures on writers—some of them very old, others newer related to online publishing and marketing—that can be so acute and harmful. The feeling that you have to get your work out there right now. That there’s something wrong if you haven’t published a book yet. There’s something wrong if you haven’t published anything for six months. It’s pernicious. I really think you should set a draft aside for a year—I’m only saying “six weeks” because I’m afraid people will freak out if I say “one year” because sometimes that’s not possible, the way publishing contracts work.

WOW: For me, the most exciting aspect of Monster Portraits is that it is unafraid. Your vision is clear and bold, and I never sensed you holding back. Are women more prone to doubt themselves in pushing the boundaries than men? What happens to women’s writing, in particular, when we let go?

Sofia: I think what happens is that we write like Gayl Jones. We write like Bhanu Kapil. We write like Alejandra Pizarnik. We write like Hélène Cixous.

There are so many fates that are worse than writing like these people! We should just go for it.

Naomi Kimbell is a writer, photographer, and filmmaker, living and working in Western Montana. Her essays have been published in The Iowa Review, Black Warrior Review, The Baltimore Review, The Indiana Review, Crazyhorse, Calyx, The Nervous Breakdown, The Rumpus, and other journals and anthologies. Her films can be viewed on YouTube, and she is currently working on a novel.