ife is a series of connections. One person leads you to the next. And if you're lucky, you meet some kindred spirits along the way who help you grow from a few simple words. Meeting Pat Matsueda was like that for me.

Pat's fresh outlook came at just the right time. I knew I was overloaded with projects and a never-ending to-do list that would make Santa Claus gasp, but I lacked the proper introspection to guide me through the growing storm. Interviewing Pat helped me center myself again. Despite all the work and projects she takes on, she manages to balance her life with simplicity, while cultivating a global view.

In a recent email, Pat said, “Some of it is written more for you than your readers, I think; that is, I tried to answer your questions, but I might have done so in a way that is too personal.”

This is another thing I love about Pat. She's very real. And as you readers know, that's exactly what we look for in our WOW! interviews—two women chatting casually. So come into our living room and join us in an inspirational discussion with this remarkable, and multi-talented woman.

Pat Matsueda was born in Japan but has lived in Hawaii for most of her life. Since January 1990, she has worked at the University of Hawaii: for two years, she was a technical editor at the university's Water Resources Research Center, editing reports, conference papers, and journal articles; and since April 1992, she has been the managing editor of Manoa: A Pacific Journal of International Writing. She has also edited and published a few of her own journals, the latest of which is Mixed Nerve, an e-zine. In January 2006, a collection of her poetry was published by El Léon Literary Arts and Manoa Books.

WOW: Aloha Pat, and welcome. We're excited to be interviewing such a multi-talented woman with so many hats. From your writing cap, editor's hat, to design, website, and photography berets, to your teaching tiara... where did you start?

Pat: Thank you for asking me to participate in WOW! I'm flattered and very pleased :)

I had a good mentor: Frank Stewart. Under his tutelage, I took over editorship of the newsletter of the Hawaii Literary Arts Council, a nonprofit group serving writers, in 1977. Over the thirty years since then, Frank and I have forged a partnership based on strong mutual interests: writing, editing, publishing, understanding cultures and countries through their literature, developing organizations that could help us realize such large goals, and so forth. For about six years in the 1980s, I had a print magazine, The Paper, and for many years he had Petronium Press, a small press whose titles included work by W.S. Merwin, Leon Edel, and William Stafford. Such projects as those were superseded by Manoa, which has become an internationally recognized literary journal and, in becoming so, consumed nearly all of our energies.

As for teaching: in late 2005, one of the English department administrators asked me if I'd teach the spring 2006 class in professional editing, a course taught, up to then, by faculty members. Though I wasn't a faculty member and was fearful of teaching, I decided to accept. I've taught the course three times now, and in the fall will probably be teaching it for the last time.

Teaching opened up a new world to me, and I am grateful for all the growing it allowed—and forced—me to do. If I thought I was self-disciplined and organized before, teaching showed me that I had much more to learn about discipline and organization. I've also had the tremendous satisfaction of introducing students to editing and publishing and inspiring a few of them to enter the field. One student recently completed a six-week publishing program in New York City; another is working as an editor at Mutual Publishing; a third is a student assistant at the University of Hawaii Press; and a fourth is on the staff of a magazine. For my spring 2007 class, I created a blog—https://edithawaii.blogspot.com—and I hope to maintain it after I stop teaching so that students can use it as a resource.

“I am fortunate that my personal life is simple.”

WOW: That's amazing Pat, and I'm sure you will be dearly missed by your students. With all the things you've accomplished, would you say that the process, going from one project to the next, was organic, or was it a conscious decision to field these new territories?

Pat: Organic for the most part. Between the time I graduated from the University of Hawaii with a degree in English and the time I started working for the Research Center, I had many jobs: receptionist, administrative assistant, promotions assistant, legal secretary, state planner, and so forth. Throughout that period, my interest in writing, editing, and publishing remained vigorous, and when Faith Fujimura, the editor at the Research Center, hired me, copyediting became my livelihood.

A large part of the thirty years that have elapsed since I graduated from the university has been spent trying to mature personally and professionally. This has been challenging, and I am still learning how to express my strong feelings and opinions in ways that serve common interests and projects. Whatever personal energy goes unused in this process is fed into such projects as my e-zines.

WOW: It's comforting to have your own creative outlet as a home for your personal thoughts. Now I have to check out your e-zines! They sound fascinating. So how do you balance all of these projects... I'll admit, multi-tasking is not my strong suit, I tend to get scattered the more I take on. How do you organize your workload to handle it all?

Pat: I'm fortunate that my personal life is simple. I live in a small apartment downtown and don't have children. Within ten minutes' walking distance are the post office, supermarket, drugstore, two of my doctors, gym, and so forth. I do drive to work, but try to avoid driving if I can (my 2001 Saturn has 28,000 miles on it).

My largest commitments are therefore to my job and my sister, a super, intelligent person with schizo-affective disorder. Recently, I convinced her to join my fitness club; we now exercise three or four times a week at the gym and go swimming as well. It seems that she is slowly regaining control over her life and herself, and that is a beautiful thing to behold.

When I am at home, I spend much of my time in front of my computer, corresponding with friends, working on such personal projects as Mixed Nerve, and trying to acquire new skills; for example, I'm trying to learn Adobe Illustrator right now. Luckily, it's a short step from bed to desk to kitchen. I also try to be organized: I have to-do lists on my computers at work and home; I try to keep important files in order; and once in a while, I'll send e-mail reminders to myself so that I don't forget to take care of small but important matters. I also give my coworkers—Frank, the head of Manoa, and Brent, our production editor—permission to nag me about office priorities.

I also try to be organized: I have to-do lists on my computers at work and home; I try to keep important files in order; and once in a while, I'll send e-mail reminders to myself so that I don't forget to take care of small but important matters. I also give my coworkers—Frank, the head of Manoa, and Brent, our production editor—permission to nag me about office priorities.

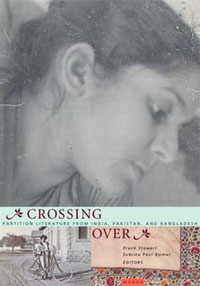

(Photo from Pat Matsueda's ‘Editor's Diary’, Mixed Nerve)

My cell phone I use as a tool: something that allows me to accomplish things or stay in touch with my sister or the office. I don't use it to socialize, preferring to either write my friends or see them in person. I love to go out for a meal and chat for a couple hours.

WOW: Gee, I thought I was the only one who disliked having a cell phone connected to my ear at all times—especially here in California! And Frank must love that ‘permission to nag’... you know, I chatted with him in a couple of emails and he can't say enough nice things about you. If I recall correctly, didn't Frank make you the first fulltime employee at University of Hawaii's Mãnoa Journal? How did that happen?

Pat: In 1987, Frank and Robert Shapard—two writers and teachers of writing at the university—submitted a proposal to then president Albert Simone, who had issued a call for the creation of new journals. They proposed an international literary journal that would do two things: bring to English-speaking readers the literature of Asia and the Pacific, and bring to these places the work of American writers. The proposal was accepted, and in 1988, production began on Manoa, the first and the only literary journal published by the University of Hawaii Press. The premiere issue, a double one, came out in fall 1989. I was asked sometime that year or the next to volunteer my proofreading services, and soon thereafter, I suggested that a copyeditor was needed.

In fall 1991, Frank and Robbie began working on the creation of a full-time editorial position for Manoa. The person filling it would have these primary duties: take responsibility for "substantively editing scholarly/literary MSS for organization, technical errors, grammatical errors, and stylistic inconsistencies"; be the journal's authority on copyediting matters; evaluate and recommend manuscripts for publication; correspond with authors, editors, translators, and so forth; select, train, supervise, and evaluate staff; and coordinate editorial work with other aspects of the journal's operations, e.g., grant writing and fund raising. In spring 1992, I was interviewed and hired as managing editor. At that time, we had one room, a PC with a 286Mhz processor, and a table that I used as a desk; Mahealani Dudoit, a student who had been working with Frank and Robbie, was promoted to associate editor.

WOW: I'm sure your office has come a long way since you were hired! At least your computer equipment. So, what are the tasks of a managing editor?

Pat: My duties are now somewhat different from the ones I was hired to perform, in part because of technological advancements. For example, we now do our own typesetting and layout, so I edit more with an eye to page and book design than I did before; we also design and maintain our own website (https://manoajournal.hawaii.edu) and have created a blog to supplement what we call the Manoa experience. Having our own website allows us to reach more people while requiring us to learn web-design tools—a slow process, I have to admit.

Grant application, administration, and reporting are now my responsibility primarily; that is, I work on these to a greater degree than anyone else in the office. Closely aligned with those duties are financial ones: preparing budgets, keeping track of income and expenses, and processing payments and fund transfers.

The staff has changed a great deal over the years, and we now have another full-time position in addition to mine: that of production editor. This means, in part, that hiring, training, supervising, and evaluating duties are shared, and we take the time to forge a consensus before making personnel decisions.

“I find it very satisfying when I can finally hold a printed copy of something I've worked on.”

WOW: You mentioned typesetting and layout as one of your duties, do you work on other design as well?

Pat: My mother was a very good artist, and my sister and I share a love of art. Under Frank's direction, I've produced ads, flyers, and other materials for the journal, indulging my love of art and design. For my friend Frankie Enos, who is the vice-president of a local theatre group, I've designed postcards, flyers, and programs. One kind of work is done for a paycheck and the other for free (most of the time); they are equally challenging, and I find it very satisfying when I can finally hold a printed copy of something I've worked on.

WOW: My mother was also an excellent artist who taught me how to oil paint when I was ten. It's amazing creating something from nothing, to see your work visualized. This is one of the things I find impressive about Mãnoa journal—the continuity with design and theme elements. At WOW! we're also very theme conscious. How do you choose the upcoming themes for your editorial schedule?

Pat: As the head of Manoa, Frank decides what our issues will focus on. For example, the winter 2007 and summer 2008 issues will explore the subject of reconciliation, rather than focus on the literature of a particular country or region, and this decision arose out of Frank's longtime study of the cultural, philosophical, and ethical aspects of conflict among individuals, communities, and countries.

In 2009, Hawaii will be celebrating its fiftieth anniversary as a state, and we will be trying to produce an issue that looks at the subject of statehood—controversial because of the path by which Hawaii became part of the union—from many points of view: economic, philosophic, social, and so forth. This project is sure to bring together diverse, and conflicting, voices and points of view.

Factors influencing Frank's choice of what an issue will be about include the writers, editors, and/or translators he's in touch with at a given time; matters of current regional or global concern; and our publishing history and mission.

WOW: After those theme elements are established, what comes next?

Pat: Frank gets in touch with someone who will serve as a guest editor—if a person hasn't already volunteered—and they will start corresponding about possible pieces. Eventually, a rough table of contents will be produced, and Frank will have a good idea of what the issue will be like—or what is lacking to complete it. Pieces will start coming in and being handed over to Brent, our production editor; he will initiate the word-processing phase of production (scanning, styling, proofing against the original) and start creating database records and publication agreements. The manuscripts will then come to me, and I will start copyediting.

“Each issue is book sized (usually 200 pages or longer) and involves collaboration with dozens of people, some of whom are in other countries.”

Every manuscript goes through two stages of editing and proofreading, and then galleys are sent to the authors. Sometimes, there is correspondence between us and the authors about the editing, and after all changes and corrections are made, the issue is printed out and assembled. Everyone proofreads the issue, and then we have a group meeting at which we go through it page by page, each person pointing out errors (stylistic, typographic, grammatical, etc.) and suggesting ways to improve sentences that need further editing. After that, the issue is typeset and laid out, and we proofread it again, though not word for word. At that point, we are in pages and working with Barbara Pope Book Design on the cover, front matter, and interior art.

Once an issue is published, we are, of course, in the middle of production on the next one. The freshly printed issue gets a big hug and lots of cooing over. We work on getting media coverage of it—distributing announcements, press releases, and review copies—and every so often we organize promotional events, such as readings and launches. These efforts complement those of the UH Press marketing department, which features Manoa in its catalogs and promotes it on the internet, at book fairs and conferences, and through sales representatives.

Of course, this is a simplified version of what actually takes place. Each issue is book sized (usually 200 pages or longer) and involves collaboration with dozens of people, some of whom are in other countries. Assembling the material may take place over the course of years rather than months, as happened with our Cambodia and French Polynesia issues.

WOW: Pat, that's amazing, and much different from an online publication. Thank you for the insight.

In my humble experience, I know many writers would like to think their work was perfect when submitting to an editor, but in most cases that's not quite true. Besides mechanics, there's the voice of the publication to consider, angles, and overall flow of the piece. When you work with a writer, how much editing do you do?

Pat: It really depends on the piece. In the cover letter we send authors with their publication agreements, we say that we will edit their work and that they will get galleys to review and approve. Authors with publishing experience usually understand the value of good editing; it is the inexperienced writer who is likely to resist editorial help. Most of our authors recognize that we are trying to get their work in the best publishable form, and they appreciate our efforts and the care with which we treat their writing.

In general, poems require little editing, though translations of poems may require extensive work. When Frank worked on a couple of the Henri Hiro translations in Varua Tupu: New Writing from French Polynesia, he did a lot of research in order to put himself in the mind of the writer, an extraordinary man. This produced fantastic results, and I benefited not only as an editor and reader but as a thinker and writer.

With an essay by an Okinawan historian about his internment as a boy soldier at Angel Island—another of my favorite Manoa pieces—Frank moved sections around and deleted a few to strengthen the narrative flow. Because of that structural work, the reader comes to the ending of the essay and finds it as quietly powerful and memorable as the writer had intended.

I tend to do less developmental or conceptual editing and to focus more on line editing and formatting, or styling as we call it in the office. In one case, I worked closely with the writer on the shape and structure of his piece, and the additional work was worth it: after publication in Manoa, his piece was selected for reprinting in Houghton Mifflin's Best American Essays, a great honor.

There have been a few times when we've rewritten pieces: a hastily composed book review; a personal essay by someone who had an important story to tell but whose command of English was weak; a translation that might have been true to the original but missed the significance of the tale. In every case, there was a good reason we accepted the work; normally, such manuscripts would be rejected.

“...we look at the world as a place where we may gratify and entertain ourselves rather than as a place where we may reach our potential for compassion, wisdom, and service to others.”

For guidance and technical matters (e.g., multiple punctuation, use of quoted material, capitalization of abbreviations), we refer to one of the industry's bibles: The Chicago Manual of Style.

WOW: Oh yes, that definitely is the industry's bible. Every writer should have a copy.

You mentioned that sometimes an essay misses the original significance, or as I call it, gets ‘lost in translation’. How do you bridge the gap? It must be extremely challenging.

Pat: The answers to these questions are best found in The Poem Behind the Poem, a publication by Copper Canyon Press of two Manoa symposia on the subject of translating poetry. In here you'll find the thoughts of translators like Tony Barnstone, Michelle Yeh, Gary Snyder, W.S. Merwin, Jane Hirshfield, and Arthur Sze. As a partial answer to your question, let me quote from Frank's preface to the book:

If there is a thread that runs through the essays, it is the willingness of translators to allow themselves to be assimilated to the poems in the original language and to poetry. Their common approach is humility.

Concerning the translation process, many assert it as a requisite to lose themselves—intellectually, emotionally, culturally—by a concentrated act of will that may take years of study and meditation, followed by a leap into a state of mind that can be described only indirectly and metaphorically. For example,

A simple surface act—that of linguistic transference—is in a sense an impossibility. The poem, the writer-translator, and language must give themselves over to the experience of death and transfiguration, in which new life appears.—Eric Selland

The translator must love poetry so much that the poems become part of his breath.—Ok-Koo Kang Grosjean

The poem becomes a part of my daily life: I dream about it, read supplemental texts, meditate on the process, learn all I can.—Leza Lowitz

WOW: Those are wonderful quotes, and Frank put it so eloquently. Besides the responsibility of the translator, a lot of times media plays a role in narrowing our view of other countries and cultures, yet the Mãnoa journal strives to bring awareness through its publications.

In your opinion, why are Americans so closed off to expansion? Do you think our media outlets have an impact on our thinking?

Pat: Yes, definitely. Because America would come to a standstill if we weren't constantly buying and getting things, our intellectual and psychological development is arrested; we look at the world as a place where we may gratify and entertain ourselves rather than as a place where we may reach our potential for compassion, wisdom, and service to others. American culture is materialistic and exploitive, and most of us are not taught to be of service to groups beyond the ones we're born into or accepted into because of our profession or economic standing.

Manoa connects its readers to places and times they might otherwise never come to know, offering them the opportunity to break out of the modes of "Western," "American," "modern," and so forth. Of course, there are many organizations engaged in this endeavor; we are just one.

“Now my favorite writers include people

all over the world...”

WOW: I can imagine you've learned a lot from working with Manoa. In your interview with the KYOTO Journal, you'd said, “Working with several hundred authors on their pieces, reading and editing work from all over the world — this has changed my thinking, even who I am. In fact, I would say I am no longer the person I was when I started.” From your years with Mãnoa, who would you say you are today?

Pat: I feel as if I have so many feelings and thoughts lodged in my heart and mind: I am weighted not only with my own history and experiences but with those of people in Tibet, Korea, Cambodia, French Polynesia, Viet Nam, the Philippines, Australia, India, Pakistan, and so forth. The stories, essays, poems, interviews, and plays I read as a result of my job mingle history, geography, and politics with literature, so I live in a richly layered, complex reality. This is Manoa's great gift to the people who work for it.

Now my favorite writers include people all over the world, and the importance of reading the literature of other countries has become so obvious that I barely have the words for persuasion. When I read Wayne Karlin's translation of the Vietnamese story "Starting Over"—which, on the surface, seems to be a simple tale—I am immersed in the country's tragedies, the sadness of its past, and like the characters in the story, I hope for a better future for the people. When I read "The Glory of the Wind Horse," a story by Tibetan writer Tashi Dawa, I am amazed, thrilled, and gratified that a story so inventive and wise has come my way.

WOW: You've experienced so many cultures and countries from working with Manoa, including your own. As you know, I'm half-Japanese, and although I wasn't born in Japan as you were, I've visited many times and have a very deep-rooted connection with my culture. I know you moved to Hawai'i when you were young, but do you feel this connection as well?

Pat: Well, I envy those visits, Angela!

My mother was a Japanese national who married a Japanese American soldier. We went back and forth between Hawaii and Japan a few times, then my parents divorced and my mother brought my sister and me here at the request of my father's parents. Unfortunately, they didn't treat her well, and we stopped seeing them. In Hawaii, my mother had a hard life because she didn't speak English well and only had a high school education. Because of our family history and circumstances, I grew up with an immigrant's sense of being outside the center; for many years, until I graduated from McKinley High School (known as Tokyo High in those days), I wanted to return to Japan.

I feel that my aesthetics, my sense of design and color, my desire to balance art and nature are all Japanese. Recently I bought two hard-cover books, both published by Tuttle: Japan Style: Architecture, Interiors, Design and Japan Houses. The second book is about expensive, elegant, modern houses, and the first about traditional houses. Modern and traditional styles both please me. However, I can see that the modern houses require large quantities of concrete, steel, and glass and are built on a different scale: they enclose large spaces and are meant to impress.

The traditional houses are smaller and are designed to welcome and calm, to integrate home life with natural beauty.

“We need to live, as the Buddhists would say, mindfully.”

WOW: Pat, we're so much alike in many ways... can you share with our readers some of the major sources of inspiration in your life?

Pat: My mother passed away suddenly in September 1989, dying of a heart attack. She is still very important to me, though, and I sometimes wonder if she would approve of the decisions I've made; I hope so.

People I admire from a distance include Maya Lin, the architect, and Ehren Watada, the soldier. I am proud of Watada because he is Japanese and from Hawaii; I wish I could have half the courage and strength of character that he does. Lin is the person I would have liked to become: an artist-intellectual who expresses the essence of an idea in beautiful architectural form.

My personal bibles include Lewis Hyde's The Gift, John Gardner's On Becoming a Novelist and On Moral Fiction,

and Dag Hammarskjold's collection of writings, the Auden translation of which I read. Hammarskjold's writing wasn't meant to be published, I believe, and some of it is personal to the degree that the reader feels intrusive. I found in it a kindred spirit: solitary, seeking its own counsel, concerned with moral questions and problems. Another bible is Mystery and Manners, a book of essays by Flannery O'Connor collected by Sally and Robert Fitzgerald after her death. I'm very interested in the thinking—the critical, spiritual, philosophical, psychological debates—that goes into the creation of art.

WOW: Your artistry takes on many forms. Previously, you published books and created a magazine. Can you tell us a little bit about them and if you're still involved?

Pat: My book of poetry, Stray, is about the choices people make and how these choices reflect their character and affect their lives. I'm most interested in those crucial moments when we make moral and ethical decisions that alter our lives. These deepen our sense of who we are, enlarge our consciousness, and increase our sensitivity to the world around us.

WOW: I'll have to pick up a copy of Stray. It sounds wonderful, and from the reviews, you've affected many reader's lives for the good. So, what are you working on right now?

Pat: I have a blog—https://mindfulshopping.wordpress.com—which I hope to turn into a place where friends can talk about the choices they've made as consumers. Because consumerism is such a large part of our lives, I feel we need to practice it deliberately, consciously, responsibly.

WOW: : I agree and am looking forward to participating. Your views are truly refreshing and nurturing... do you have any closing comments for our readers?

Pat: We need to live, as the Buddhists would say, mindfully. I try to do that, but I sometimes find I need something—like a setback or an illness—to make me stop and look honestly at who I am and why I do what I do. The truth about ourselves is often the most difficult thing for us to see—and that's why I write.

WOW: Thank you Pat for sharing your wisdom with our WOW! readers. You are a tremendous inspiration to me, and I'm sure to women writers everywhere.

To find out more about Pat Matsueda, please visit:

Mixed Nerve: https://mixednerve.org/

Mindful Shopping: https://mindfulshopping.wordpress.com

Edit Hawaii: https://edithawaii.blogspot.com

Manoa Journal: https://www.hawaii.edu/mjournal/

Pat Matsueda's Home Page: https://homepage.mac.com/pmatsueda/