icture this: Me, a writer, bent over my work like a surgeon—critiques sprawled across my desk like x-rays; my finger poised on the delete key. The mangled manuscript on my laptop looks nothing like the healthy novel I envisioned. I stare helplessly at one scene, stitched on like a poorly fitted prosthetic. Elsewhere, there’s a gaping hole from an emergency chapter-ectomy. As I dissect the latest incarnation of my novel, it’s all I can do not to raise my carpel tunnel-syndromed hands to the sky and shriek, “It’s ALIVE!” All evidence points to the fact that I have, in the words of Kate Sullivan, editor at Little,

Brown Books for Young Readers, totally “Frankenmonstered” my manuscript.

But how? How did it come to this? I have solid characters and a compelling plot. Where did it go wrong?

I glance at the craft books littering the floor at my feet, the helpful notes of my beta readers (my sixteen-year-old son and some random guy I met at Starbucks who claims to love quirky middle-grade fiction), and back to the responses of my critique group. I’ve applied them all religiously and followed every suggestion to the letter. My creation should be perfect. Sadly, it is not. It is an abomination. I unstrap it from the table and cast it aside.

Open new file.

Start over.

If this image of manuscript as monster seems familiar to you, don’t worry. You’re not alone. Many writers jump into revision with complete confidence only to find themselves alone in a dark room with their maniacal manuscript staring back via the eerie glare of a computer screen. It has happened to me (more than) once; and in fact, I was so desperate last year that I wrestled my manuscript into a suitcase and flew to New York in search of answers.

I sat in a conference surrounded by writers who all seemed way too calm to have flown in with anything less than perfect novels. But it was there, at the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators Annual Winter Conference, that I first heard the words that put me on the path toward taming my manuscript. Kate, Little, Brown editor extraordinaire, cautioned conference attendees to carefully weigh critique advice before trying to implement it. Her words still echo in my head like the proclamations of seraphim: “Accepting every suggestion you’re given can create a schizophrenic manuscript.”

“Accepting every suggestion you’re given can create a schizophrenic manuscript.”

(Photo: Kate Sullivan)

I knew right away that she had just diagnosed my work in progress. But that raised another question: Short of putting my manuscript on a Thorazine-Haldol cocktail, what could I do? Since editors usually don’t appreciate being locked in elevators until they cough up the perfect prescription for an ailing novel, I decided to take the question back to my writing colleagues.

Jody Lamb, whose middle-grade novel Easter Ann Peters’ Operation Cool was just released by Scribe Publishing, told me she had a similar experience around draft two. She was a member of three critique groups and participated in frequent workshops. Feedback and advice about changes to plot, pacing, character development, and dialogue varied greatly. “There were so many opinions to sort out,” Jody explains. “I lost confidence in my ability to make decisions about the story. I second guessed everything I wrote.”

At a conference, an editor from one of the big publishers told Jody that in this age of wizards and vampires, middle-grade realistic fiction is difficult to sell. In order for her manuscript “with a great voice” to be more appealing to publishers, she needed to change the plot and the characters—drastically.

“I couldn’t and wouldn’t change the story the way that editor advised,” Jody recounts. “It would have destroyed the story’s tenderness and its whole purpose. At that moment, I reminded myself to pay more attention to my heart than what the publishing industry editors and agents say about what they’re looking to be the next big hit. I wrote and revised the story I wanted to read and would have been moved by as a tween.” That realization helped Jody become more effective at deciding what feedback and advice to use and what to politely ignore as she wrote two more drafts. Easter Ann Peters’ Operation Cool was rejected thirty times by agents and editors before being accepted by Scribe Publishing Company’s founder, who believed in the story and the author. “Let your heart guide your decisions,” Jody advises.

“Let your heart guide your decisions.”

(Photo: Jody Lamb)

Kate agrees, stating revision should be “a balance between trusting your vision for the manuscript and accepting advice that sounds right for that vision. As an editor, I’m going to give you suggestions for making this the best book according to your vision. Not all of my ideas will be perfect.” Kate warns that “a manuscript becomes schizophrenic when an author takes advice a little mindlessly—makes a change without thinking about it, without understanding the change.”

That’s not to imply that writers don’t agonize over each decision, just that sometimes it’s hard to see the ramifications one little change can have for the overall structure of a work.

That was certainly the case in my Franken-novel. I’d removed a few characters that seemed extraneous, but failed to fill in the holes left by their absence. Why did I leave the gaps? It wasn’t out of laziness or haphazard editing. I left them because I didn’t even notice they were there.

Barbara Shoup has been teaching writing for over thirty years and even with the release of her seventh novel, An American Tune, she admits still being blind to some things in her own work. “Writing is like translation,” Barbara says. “What you know is not in words, what you see in your mind’s eye is not in words, what you feel in your heart and gut are not in words—but words are all we have to tell a story. So you have to translate your evolving story into words. The trouble is when you’ve done this to the best of your ability, you’re incapable of really seeing what you’ve accomplished because you can’t separate what’s in your head from what you managed to get on the page.” That’s where feedback is vital.

Barbara continues, “A good critic helps you see the difference [between what’s in your head and what’s on the page]. She asks questions, makes observations that help you identify where you’ve gotten it right and where you still have work to do.

“It’s very important to be sure that the person offering a critique understands what you’re trying to do with your work and isn’t trying to redirect you toward writing the kind of novel she’d prefer,” Barbara cautions. She goes on to suggest that as writers sift through the advice they receive, they should look for “insightful comments that trigger their own insights about how to do what needs to be done.”

“It’s very important to be sure that the person offering a critique understands what you’re trying to do with your work . . .”

(Photo: Barbara Shoup)

That echoes Kate’s process for working with authors. “I may give seven suggestions. If you implement four that really resonate, that may fix the three that didn’t. Fixing a chapter where the plot didn’t work may fix a character issue later in the book. Issues are intertwined.”

It’s exactly that intertwined-ness of issues that had caused me to run screaming from my manuscript. All of that is great advice for writers approaching revision, but what about those of us who have already made a complete mess of our manuscripts? This is where the Dr. Phil in my head pipes up. “Put some verbs in those sentences, people!”

Kate has this to say:

If a writer has that ‘come to Jesus’ moment, where you realize you’ve Frankenmonstered your book, it is hard to go back in and approach it line by line. In an over-edited copy, you’re seeing all the bad stuff. You have two options: One, go back to an older draft. Reread in original, distilled form to see what worked. Which of the edits do you miss? Two, throw it out and start over—I know, that’s torture. But pinpoint the specific part that doesn’t work; write it fresh. Good ideas stick with you, so you naturally incorporate the really great ideas. Trust memory to reinstill the good stuff.

Starting over works for Jody, who says, “I actually start nearly from scratch with each draft, leaving behind the lousy and enhancing the good.”

As for going back to an earlier draft, that only works if you have a system for how you save drafts. The first novel I wrote (lovingly nicknamed Trunk Novel #1) took twenty-four drafts before I realized it would never be publishable. Part of the reason the novel unraveled so disastrously is because I had no system for organizing my drafts. My critique group at the time assured me that I did not have to kill my darlings; I could just cut them from the current draft. Then I’d always have them in case I wanted to use them elsewhere.

So each time I cut something, I saved the new version as a separate document. And—can you see this coming?—I called them draft #1, draft #2, etc. None was a full draft. Each represented some small change. Learn from my mistake: Create a better system for organizing your drafts. Name one draft “1st person POV—Chris,” another “3rd person POV.” Be sure to date each draft, so you know which one is most recent. Some programs have built-in features that allow writers to keep track of drafts or even to merge multiple drafts. I’m not there yet, and neither is Barbara, who prefers a traditional spiral notebook, where she keeps track of drafts and works things out as she goes.

Whether you use a program or a pen and paper, organization is also vital in how you approach revision itself. Many first-time authors approach revision by starting at page one and working through to the end. On every page, they attend to every detail, trying to “fix” it all at once. That may work with a short piece; but when you’re dealing with an entire novel, it can quickly get overwhelming because you cannot hold an entire novel in your head at one time. Think about all the nuances of character development and the intricacies of plot and pacing. It’s a lot like trying to study Kilimanjaro through a wide angle lens. To fully understand the majesty of the mountain, you need the context of that panoramic view; but to comprehend life on the mountain, you need to break out the telephoto lens. Novel revision is the same thing. Zoom in to study the microcosms within your novel.

Choose one—like dialogue—and focus on just that for a whole draft. As you make changes in that one area, you will notice other things that are affected by those changes. Take notes, so you can go back and address them later. Possible microcosm of novel revision: character arc, plot, dialogue, setting, pacing, point of view, tension, sub-plots, etc.

“It’s a lot like trying to study Kilimanjaro through a wide angle lens. To fully understand the majesty of the mountain, you need the context of that panoramic view; but to comprehend life on the mountain, you need to break out the telephoto lens.”

Another approach I find extremely helpful for revision is reverse storyboarding. I discovered the technique quite by accident after I’d pretty much given up on my failed manuscript. In an attempt to move on, I attended a workshop on storyboarding led by Cathy Day, author of The Circus in Winter. Prior to this I’d avoided storyboarding, partly because I am illustratively-challenged and the idea of trying to visualize my story by sketching the scenes sounded much more difficult than just writing the darn scenes. But I recognized that I needed some sort of plan going into the next novel. Storyboarding seemed like a strategy that would provide enough structure to prevent another Frankenmonster while remaining loose enough to accommodate the organic nature of my writing.

Cathy won me over when she demonstrated that I didn’t have to be able to draw in order to storyboard—I could verbally sketch the scene.

(Photo: Cathy Day)

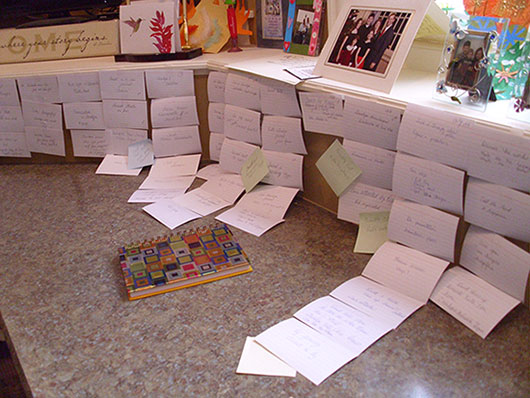

As an introduction to the storyboarding process, Cathy first guided the participants in her workshop through reverse storyboarding a published work. Her goal was to force writers to analyze the structure of a successful story in order to learn how to effectively use that structure. In essence, reverse storyboarding requires a writer to break apart a work using index cards to “thumbnail” each scene in the book: identifying the who, what, where, why, and how of each scene. Distilling the book into these snapshots allowed us to determine the major plot points of the story. Once we had done that, Cathy led a discussion regarding how the author used that story structure. If you’re considering the approach with your own work in progress, please view Cathy’s website, where she has graciously mapped out her reverse storyboarding approach in much more detail.

As the class moved onto storyboarding our current works in progress, I kept thinking how reverse storyboarding might be just the right prescription for my Franken-novel. I bought two packs of index cards and some sticky tack on the way home, locked myself in my office, and took all the pictures off one wall. Three days (and another pack of index cards) later, my Franken-novel had the correct number of limbs, no gaping holes, and a sturdy spine to support it. It still wasn’t ready to be released into the village, but at least it could walk on its own.

What makes reverse storyboarding so effective is it allows writers to break the novel down into its components while still seeing the big picture. Back to the Kilimanjaro metaphor—it’s like assembling those close-up shots of life on the mountain into a mosaic of the whole mountain. According to Cathy’s blog, The Big Thing, reverse storyboarding allows writers “to figure out how [novels] work, how they will read, how to set up the effect they want the book to have.”

No one approach works for all writers, so play around with a few of these tips to see if they work for you. Remember, though, as you experiment, attempting too many revision strategies is a form of procrastination; and if you’re not careful, it can turn a reasonably tame story into your very own Frankenmonster.

***

Katherine Higgs-Coulthard is founder and director of Michiana Writers’ Center in Indiana, a fun job that provides just enough income to support her addictions: caramel macchiatos and frenzied bursts of caffeinated fiction writing. You can visit her at https://www.writewithkathy.com or https://www.michianawriterscenter.pbworks.com.

-----

Enjoyed this article? Check out more from Kathy on WOW:

The Energizing Spirit of Transition: Divergent Paths to Publication

Unearthing Precious Ideas: Literary Agent Regina Brooks

The Smell of Success: Transitioning the Pen and Paper Crowd to E-Books

How to Trim the Fat from Your Manuscript

Channeling the Voice of Youth: Interview with Ellen Hopkins

-----

You may also like:

Shedding Light on the Role of the Beta Reader