t's a common misconception that editors won’t deal with authors directly. Not only will they interact with you, but they’ll buy your book. I know this for sure because it happened to me. I had three agents try to sell my humorous memoir, Running of the Bride, with no luck for over two and a half years. As a last-ditch effort before shelving the project, I decided to represent myself—and sold it in fifteen days. Here are ten tips on how to sell your own manuscript.

Have a book worth buying. This is two-fold. First, you need a strong, saleable idea. Make sure that you’re filling a niche, however small, and there is an audience for it. An editor will be hesitant to buy a book that doesn’t have a built-in and defined readership. Secondly, you need to present your very best work. Most editors will only give you one shot, so you’ll want to make sure your materials—a full draft if fiction or minimally, a proposal and three sample chapters if nonfiction—are their most polished. Consider hiring a freelance editor, bringing your work before a writing group, or asking a trusted friend for comments.

“You need to demonstrate that you’ve invested in yourself . . .”

(Photo: Christine Clifford)

Get your name out there. Start promoting yourself before your book sells, so a potential editor can see that you’re committed to success. You can do this through traditional venues—like industry blogs or newspaper and magazine bylines—or less traditional venues, like a cheeky petition to get your book on shelves. Persistence is also key. It paid off for Christine Clifford, who has sold seven unagented books, including the bestselling Not Now . . . I’m Having a No Hair Day (University of Minnesota Press) and You, Inc: The Art of Selling Yourself (Grand Central Publishing)—the latter of which scored her and her co-writer husband a $250,000 advance.

She notes that one of the most important factors when trying to sell your manuscript unagented is that “you need to demonstrate that you’ve invested in yourself and therefore, will invest in the publisher and your book. It helps immensely to have a platform, such as a speaking career, from which to promote your book.”

Network. You’ve heard this before and for a good reason: it’s sound advice. You never know who knows whom. If you don’t tell everyone you meet about your book, you’re less likely to find someone with a best friend or second cousin who works at your dream publishing house and would be willing to look at your project. But don’t limit yourself to random encounters. Part of the reason writing conferences and workshops exist is for acquisitions editors to find potential authors. One such editor, Erin Lale of Eternal Press and Damnation Books, explains that agents “sometimes tell authors they can place their books because agents have personal relationships with the editors. You don’t need an agent for that; like many other acquisitions editors, I hear pitches at conventions.”

This works favorably not only for editors but for writers, such as Janice Booth, author of Only Pack What You Can Carry (National Geographic), who “pitched (and sold) my first book to the VP and editor-in-chief of National Geographic, who happened to visit a month-long writing workshop I’d attended.”

“ . . . like many other acquisitions editors, I hear pitches at conventions.”

(Photo: Erin Lale)

Research editors. If there’s ever a good time to be an Internet lurker, it’s now. Invest in a Publishers Marketplace membership for useful tools, such as industry-wide contact information and a round-up of books editors are buying. There are also several ways to go the free route. Use the “Look Inside” feature on Amazon and find out who edited books you admire. (Or better yet, buy books you admire.) Play around on web forums where authors congregate to talk shop. What’s important here is that you pinpoint editors appropriate for the book you’re trying to sell. I came across dozens of smart, snarky editors whose skills would have been perfect for Running of the Bride,

but they focused primarily on fiction. Cap your initial list at twenty, and do not include more than one editor from any particular imprint. (You can pitch another editor there if and when the first one passes.) Editor Erin Lale promises that authors “who are willing to spend the time to study our website . . . can do just as good a job as an agent,” and this is true of editors at other publishing houses as well.

Find a cultural tie-in. A timely cultural tie-in, which you’ll include in your query letter (see below), will help build credibility that the time for your book is now. It also lends editors subtle insight into whom you view as your readership. Did you write a romance novel? Reference all the reality shows that deal with love and dating. Write a thriller? Reference a recent crime that captivated the nation. My memoir is about my wedding, and I began sending my queries out the day Prince William and Kate Middleton got married. This allowed me to capitalize on the power of a media trend to better position myself and my work.

“Do not mention why you don’t have an agent.”

Write a convincing query. The only rule here is to be professional. Your relationship with an editor will evolve, and you might segue into a more relaxed tone; but you want to show that you’re capable of representing yourself and your book in a serious way. That said, there’s no magic formula. My query for Running of the Bride was under 300 words and broken down into an introduction to the book, a timely cultural tie-in, a list of credentials, and a short housekeeping paragraph. (“I have attached my proposal and sample chapters for your review and would be happy to send the full manuscript, which I am offering to a small group of publishers, at your request. Thanks in advance for reading.”) I’m certainly not saying that my approach is the best or only one to consider. Do what works for your manuscript and stay realistic.

No editor wants to hear that you’re the next E.L. James. It’s a pompous claim—however true you think it is!—and can easily turn an editor skeptical. Also, do not mention why you don’t have an agent. If an editor wants to know, she’ll ask. Some of the editors on my top twenty list did ask, and I was able to share my story with them at the appropriate time. When you send your query, include, as I mentioned I did in my housekeeping paragraph, your proposal, first three chapters, and/or full manuscript, depending on your genre. (See below for one exception to this rule.)

Follow instructions—sometimes. Erin advises all unagented authors to “read the submissions guidelines: don’t bother sending a book of poetry to a company that is closed to poetry submissions; and if the guidelines say to include a marketing plan for your book, do so.” These are good instructions to follow. Sometimes, though, it’s okay to break the rules. For instance, some publishing houses will say that they do not accept unsolicited submissions. Several of my top twenty editors had such stipulations on their websites, but I worked around it because it didn’t say that they do not accept queries. I sent my query without attaching any supporting materials and almost all wrote back with interest. I could then send them my materials because the editors specifically requested (i.e., solicited) them.

Follow up—always. Janice, the author who signed her first book to a National Geographic editor she met at a writing conference, can attest to this. “I followed up with a proposal, sample chapters, and ideas,” she says. “And three months later, I had an offer and advance.” Give editors one month before you send a polite e-mail nudge. Break this rule only if you hear from an editor who’s interested in your work before the one-month mark. In that instance, you’re free to nudge others to whom you’d already reached out with the idea that you’re hoping to make an informed decision. For example, I was able to write my now-editor to say that Avon and St. Martins had both been corresponding with me about a potential acquisition, which made my manuscript that much more attractive.

Knowing they’re up against competition can be an effective tool in convincing editors to lock down an offer. Big, huge word of caution: never, ever lie about another imprint’s interest in your manuscript. Publishing is a small world, and editors know each other. Plus, who wants to build a professional relationship on a falsehood?

“I followed up with a proposal, sample chapters, and ideas. And three months later, I had an offer and advance.”

(Photo: Janice Booth)

Don’t cold call. I’m not telling you that there will never be an instance where an editor will engage a cold caller. But I am telling you that it is hard to captivate someone, especially a busy someone, who has never heard of you or your work. Christine, the bestselling author with the $250,000 advance, suggests looking for ways to warm up that cold call. “Dig as deeply as you have to dig to find some type of connection to that publisher or editor before making your call,” she says. “Perhaps it’s another book they published, and you know the author. Or a mutual friend has suggested you contact them. Do your research and homework.

Find out where they grew up, went to school/college, where they worked before they landed at the publishing house they are currently at, where they live now, etc., so that when you finally make ‘the call,’ it isn’t cold.” There’s also a simple logistics game at play here: Many editors in mid-level and smaller houses telecommute. Erin notes that if someone calls Eternal Press or Damnation Books, the person would never reach her because she works from home—a home that isn’t even in the same state as the companies.

Join a professional writer’s guild. Once you’ve received an offer, you’ll need to sign a contract. Hiring a specialized attorney to review your contract can cost $500 or more. Instead, consider joining a professional writer’s guild. One of the most prestigious is The Authors Guild, which provides access to a lawyer who will review your contract and offer suggested changes. (It’s important to note that most large publishing houses will not change a contract in any significant way for a first-time author, even if the manuscript came from an agent.) The Authors Guild also hosts promotional workshops, builds free websites for new members, maintains a member database, and announces new books in its quarterly newsletter, among other services. The Authors Guild only accepts members who are under contract or have published a book.

Selling a manuscript can be harder than writing it. But with the proper tools at your disposal, you have as good a shot as any writer.

***

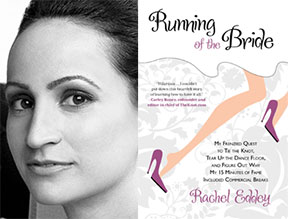

Rachel Eddey is the author of Running of the Bride: My Frenzied Quest to Tie the Knot, Tear Up the Dance Floor, and Figure Out Why My 15 Minutes of Fame Included Commercial Breaks. Join her on Twitter, Facebook, or at any dive bar in New York City.

-----

Enjoyed this article? You may also like:

How to Write a Nonfiction Book Proposal

How to Pitch a Literary Agent at a Writers' Conference